Can a medium to large organisations or businesses have wicked problems?

In a thought-provoking article in 1973, HWJ Rittel and MM Webber coined the phrase ‘wicked problems‘ to describe a particular type of social, government or policy planning challenge.

They used the word wicked not because they thought these types of problems were ethically deplorable but to describe them in terms of being vicious, malignant or tricky.

One of their key insights was ‘the kind of problems that planners deal with – societal problems are inherently different from the ones faced by scientists and some classes of engineers.

Planning problems are inherently wicked.‘

In their 1973 article Rittel and Webber also compared tame problems with wicked ones.

A tame problem ‘is well defined, with a single goal and a set of well-defined rules. (Coyne, R. 2004).

A wicked problem by contrast was very different in scope, size and complexity.

As Richard Coyne notes, wicked problems are:

– Loosely formulated

– There is no ‘stopping rule.

– Wicked problems persist, and are subject to redefinition and resolution in different ways over time.

– They are are not objectively given but their formulation already depends on the viewpoint of those presenting them.

– There is no ultimate test of the validity of a solution to a wicked problem.

– The testing of solutions takes place in some practical context, and the solutions are not easily undone (Coyne, R. 2004).

But can we extend the concept of wicked problems to organisations and businesses?

Is it not the case that certain problems like the number of female CEO’s or Equal Pay or Employee Engagement are multifaceted, complex, and extremely difficult to solve?

These sound and feel like wicked problems.

Why this is important.

Identifying wicked problems is vital for leaders because these types of big, important challenges by their very nature cannot be solved by traditional, cause and effect, linear thinking.

It’s not a question of intent, motivation or effort but what is needed is a completely new mindset, process and tool kit.

Think of a difficult maths problem for example.

With the right training, some practice and expert guidance most people could learn how to improve their maths ability and solve difficult problems.

But now think of organising a wedding for example.

There is no set formula, often competing aims (e.g. parents wanting to invite all their family and the soon to be married couple want a small, intimate wedding) and a whole series of complex, interconnected decisions to be considered (e.g. location, venue, time of the year, food, music, speeches etc).

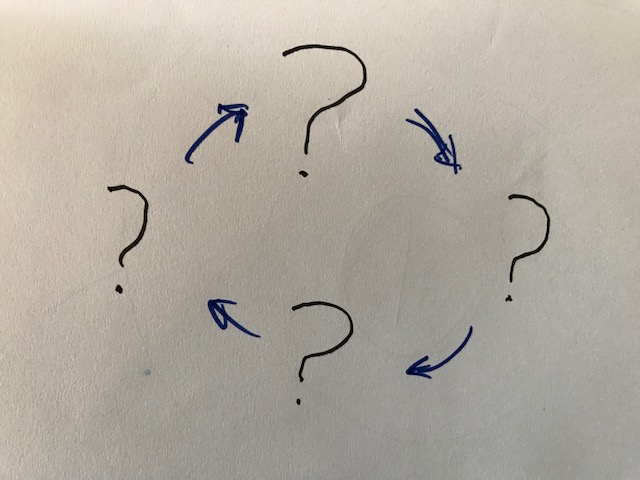

Wicked problems require a new approach.

I call this Wicked Thinking.

In future posts I will start to outline some of my initial ideas on Wicked Thinking